Going on a Treasure Hunt Week 3 of 4

In 2013, a couple was walking on their property in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. As they walked, they swung the head of a metal detector from side to side just above the surface of the ground. At one point on their walk, the detector went off, signaling that it had uncovered a piece of metal. The old can they detected could have been nothing more than a discarded piece of junk, but upon further examination, the couple discovered it was filled with Coronet gold coins–$20 double eagles– dated between 1855 and 1894. After using the detector again, the couple unearthed 8 old cans containing a total of 1,427 coins.

This treasure became known as the Sierra Ridge Hoard. The couple remained anonymous for fear that other metal detector-wielding treasure hunters would flood their property in search of more coins. According to the Coin World website, the coins were worth $10 million.

3 of the 8 cans from the Sierra Ridge Hoard © Coin World

Metal detectors have uncovered many other treasures over the years. Terry Herbert used one in 2009 to discover the Staffordshire Hoard, which consisted of 4,600 gold and silver coins from the Anglo-Saxon period. It was worth $4.3 million. An anonymous metal detector aficionado found a Henry III penny in Devon, England. While it was only a penny, it was only one of 8 Henry III pennies in the world and it sold for $880,904.

While the couple who discovered the Sierra Ridge Hoard realized they were holding a powerful detecting machine in their hands, they may not have realized that walking next to them was one of the world’s greatest detection “devices”—their dog.

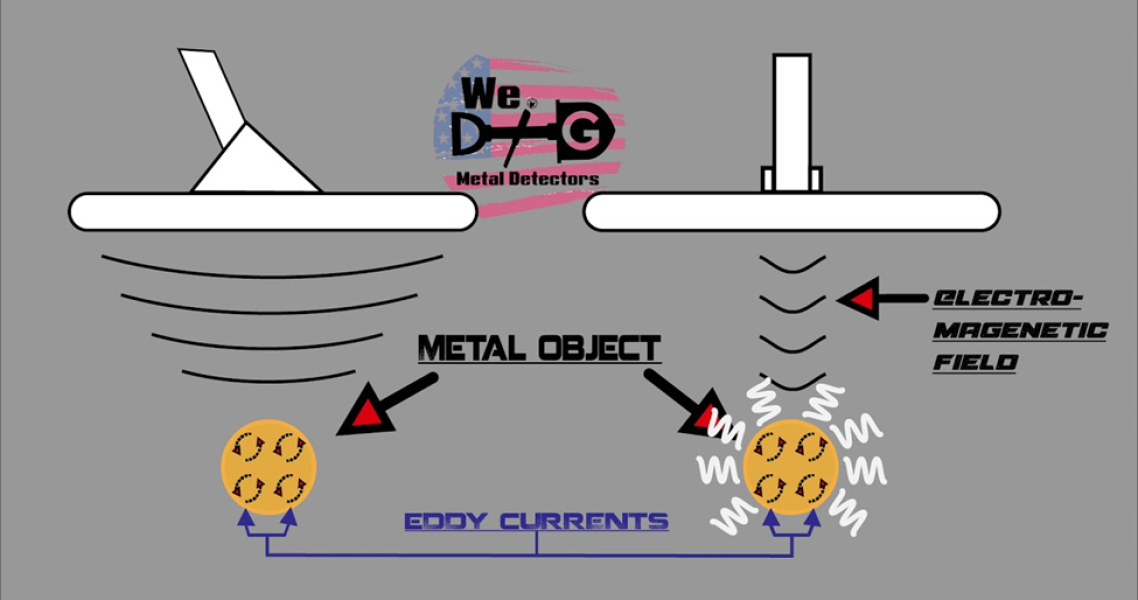

Think about how a metal detector works. The person holding the machine sweeps it back and forth just over the surface of the earth. The metal detector transmits an electro-magnetic field into the earth. When it passes over a metal object, the metal becomes energized and transmits its own electro-magnetic field back to the detector.

How a Metal Detector Works © YouTube

The world’s greatest detection device-the dog-moves its nose back and forth over the ground in a similar sweeping motion. But instead of picking up an electro-magnetic field, it picks up a scent. The dog’s nose is one of the most powerful scent detectors on earth. Where we have 6 million scent receptors in our nose, a dog can have up to 300 million. The part of the dog’s brain that processes scent is 40 times bigger than ours.

When a dog’s nose sweeps the ground, it exhales, kicking the scent up into the air. Dogs have a Jacobson’s organ in the roof of their mouth that helps them process smells. Bloodhounds, which are used to help track people, can pick up a scent from 1.6 miles away in certain situations.

The Nose Knows © News Medical

When we enter a kitchen where someone’s been baking, we smell cookies. When dogs enter the same kitchen they smell the ingredients—the flour, eggs, and sugar. Yes, dogs can see us, but they identify us by our smells. To a dog, your smell is distinct from mine. This superpower is like x-ray vision in a way. They can smell beneath the surface. If you have ever suspected that your dog just knows when you are mad or glad, they do. They can smell the cortisol that your body produces when it is under stress and the serotonin you release when you are happy. Dogs can be trained to sniff out tuberculosis, cancer and other diseases.

In the search for the saola, metal detectors will be of no help. Dogs on the other hand will be integral. In the Saola Foundation’s search for nature’s most elusive treasure, we have partnered with Working Dogs 4 Conservation (WD4C), one of the world’s foremost organizations that trains dogs to help with conservation work.

WD4C has trained dogs to detect snares set in the wild. They have been trained to sniff out poisons used by poachers as well as their weapons. Dogs have been trained to sniff out invasive plants, even before they sprout. They can sniff out microbes and bacteria. Three of the main duties WD4C trains dogs to help with according to their website are:

1. Help reduce and eliminate wildlife crime

2. Stopping invasive species

3. Monitoring elusive species.

Wildlife crime involves the smuggling of either live animals or their body parts. Dogs are used at airports and checkpoints to sniff out elephant tusks mixed in with a load of timber or a piece of rhino horn or pangolin scales hidden in a suitcase. They can sniff our live animals such as birds or reptiles.

A key to stopping the spread of invasive species is to detect and stop them early. WD4C has trained dogs to sniff out zebra mussels at boat inspection sites, stopping them before they spread to the next lake or river.

But the part of WD4C’s mission that is most applicable to the search for the saola is the monitoring for elusive species. It is like they wrote that part of their mission with saola in mind. This should make the search for the saola easy. Teach a dog what a saola smells like and then let them start sniffing away in the Annamite Mountains. This is where the challenge begins.

© Working Dogs 4 Conservation

All great treasure hunts contain clues. The saola periodically leaves behind clues in the form of poop. If you’ve ever seen your dog react when it finds a piece of poop, you know that for them, poop is olfactory gold. But if you don’t have saola poop handy to teach the dogs with, it presents another challenge.

Saola are a type of ungulate, or hoofed animal. The first step is to teach the dogs to sniff for ungulate poop. When a piece is found, the Lao dog handlers will test it on the spot to determine which species it belongs to by testing the DNA inside. Once a piece of saola poop is found, the dogs will be trained on that specific smell.

WD4C and the Saola Foundation are hiring and training local Laotians to serve as the dog handlers, including Vatsana, who will serve as the team lead.

Vatsana, in the purple coat, along with one of the dogs she trains with.

Once fully trained, this team could be employed to not only search for saola, but many other rare species in Laos.

The search for the saola will be difficult. There are most likely less than 100 saola left living in an area the size of New Jersey. The saola’s habitat is dense rainforest. But we are employing nature’s greatest search device in the search for one of nature’s greatest treasures. Imagine how much serotonin the dogs will smell when their handlers realize that the poop they just found belongs to a saola!

Training dogs and their handlers to search for the saola is not cheap. The cost of the search is $1,000 per day. I am trying to raise enough to cover 2 weeks of the search. My wife and I have Day 1 covered and are hoping you will consider a donation to help cover some of the rest. To donate or to sign up for the saola newsletter, please go to www.saolafoundation.org. Thank you to everyone who has already donated. If you would like to share this email with friends, please feel free to forward it to them.